What toothbrushing tells us about foundation models for economics

What do language, the economy, and the weather all have in common? They are all complex systems.

Nobody really agrees on what makes a complex system “complex,” but it’s generally accepted that complexity arises out of many interdependent components interacting in nonlinear ways.” — Duncan Watts

Complex systems have traditionally been hard to understand, but transformer-style models are crushing benchmarks left and right, in domains like language (GPT-4), weather (Prithvi WxC) or even genetics (Evo). These achievements are enough to make you wonder whether we might be on the verge of understanding (perhaps) the most complex of all human creations -- the economy.

Just as existing models predict the next word or the next temperature, what we would want is a black box model that would take in large amounts of data and output accurate predictions for future states of the economy. Such a model could unlock a golden age of human prosperity by finally solving the socialist calculation problem. Why, then, do economists seem to be ignoring this massive opportunity?

1. Economists make simple models.

What exactly is the discipline of economics? A superficial answer might center around markets and finance, but this is too limited. An economics textbook might explain that economics is the study of how to allocate limited resources, which captures some sense of its generality. But an even a better way to define economics might be based on its methods. The general applicability of such methods explains why it’s possible for economists, like Steve Levitt of Freakonomics, to study everything from real estate to parenting to sumo wrestling.

So what exactly are the methods that make economics distinct? As Dani Rodrik points out in Economics Rules, economics relies primarily on the creation of models. A perfect example of this is Alan Blinder’s 1974 paper “The Economics of Brushing Teeth,” published in the Journal of Political Economy. In the paper, he presents a human capital model of toothbrushing, which explains differences in toothbrushing behavior based on the incentive to maximize personal income. This model makes some useful predictions, such as that waiters will brush their teeth more often than chefs, both because waiters make more money when their teeth are clean and because chefs make more money and have a greater opportunity cost for brushing. Blinder goes on to construct a theoretical model of toothbrushing and validate it against a regression model based on a (fake) survey conducted by the Federal Brushing Institute.

This paper provides a great example of an economic method: it specifies its assumptions (that people seek to maximize income), clarifies the mechanisms driving toothbrushing behavior (opportunity cost of brushing time and importance of toothbrushing to income), and creates a theoretical model based on the assumptions that makes general conclusions provided the assumptions are satisfied.

To see why this approach is distinct, it’s useful to imagine how a psychologist would approach the same question of toothbrushing behavior.

In fact, we don’t have to guess, because I found a paper by a psychologist about the same topic. It’s called "Factors Influencing Children’s Tooth Brushing Intention”. In this paper, the authors apply a theory called the Theory of Planned Behavior, or TPB, which explains behaviors as a combination of 5 factors: intention, attitude, perceived control, subjective norms, and self-efficacy. They measured these attributes using a combination of direct (”I am going to brush my teeth,” agree or disagree) and indirect (”how bad does a toothache feel (1-5)?” and “how much does brushing affect toothaches (1-5)?”) measures.

By running a regression between these variables and brushing behavior, the authors of the TPB paper conclude that this theory does a good job of predicting the data among a set of 867 schoolchildren from Northern Ireland. They point out that motivations like “clean teeth” (duh) were strongly correlated with toothbrushing intentions, and that the opinions of trusted adults — particularly “daddy” (r=0.36) — also improved toothbrushing intentions.

Although this psychology paper may not be groundbreaking, it suffices to show some major differences between common economic and psychological methods:

- Simple vs. Full Models of Behavior: Blinder’s economic approach seeks a highly simplified model of human behavior, in which one motivation (in this case income maximization) determines toothbrushing. Davison et al’s psychological approach seeks a full model of human behavior including dozens of potential motivations and beliefs.

- Dataset Size vs. Detail: Blinder’s economic paper works from a large (albeit fake) dataset of ~18000 adults with just a few variables collected for each adult, whereas Davison et al’s paper works from a small dataset of ~900 kids with many datapoints collected on each kid.

- Specific vs. General Conclusions: The psychology paper concludes that TPB is a good way to study brushing teeth, whereas the economic paper concludes that human capital theory helps us understand. Their implications are totally different — if getting people to brush teeth more, the psychologist would probably focus on educating dads so that they could tell their children to brush, whereas the economist might implement a means-based tax to incentivize tooth brushing (cancelling out the opportunity cost!). Notably, only in the economics paper is it clear that you must assume the income-maximizing motive for the model to hold — the psych paper doesn’t clarify its core assumptions, making it uncertain how the result might generalize.

Of course, these comparisons are all caricatures of what a general psychologist or economist would do. But they are not without their truth — from my readings in social psychology, seldom do psychologists offer simple models of human behavior, instead focusing in high resolution on the motivations of individuals. Meanwhile, as Dani Rodrik writes in Economics Rules, economists are generally happy to make egregious oversimplifications about human behavior as long as they help them isolate a causal factor.

This seems to be a key trait of economic models — by making simplifications, they seek to isolate a causal factor (like income maximization) from other, confounding factors (like what your mom says about toothbrushing).

2. Economists make complex models too, but those rely on heuristics.

Now imagine if a complexity scientist decided to study brushing teeth. They might take the following approach:

- Define different properties of agents (e.g. waiter, chef, poor, rich, etc.) based on the independent variables you want to test.

- Define certain heuristics about human behavior (like “More likely to brush teeth if my dad brushes his teeth” or “ More likely brush teeth if I work in client-facing jobs”)

- Calibrate these heuristics based on a psychological study like the one above

- Simulate an environment with lots of agents who use such heuristics to make decisions about brushing teeth, and watch as they influence each other into tooth-brushing behavior.

Here’s how complexity scientist Doyne Farmer might explain it:

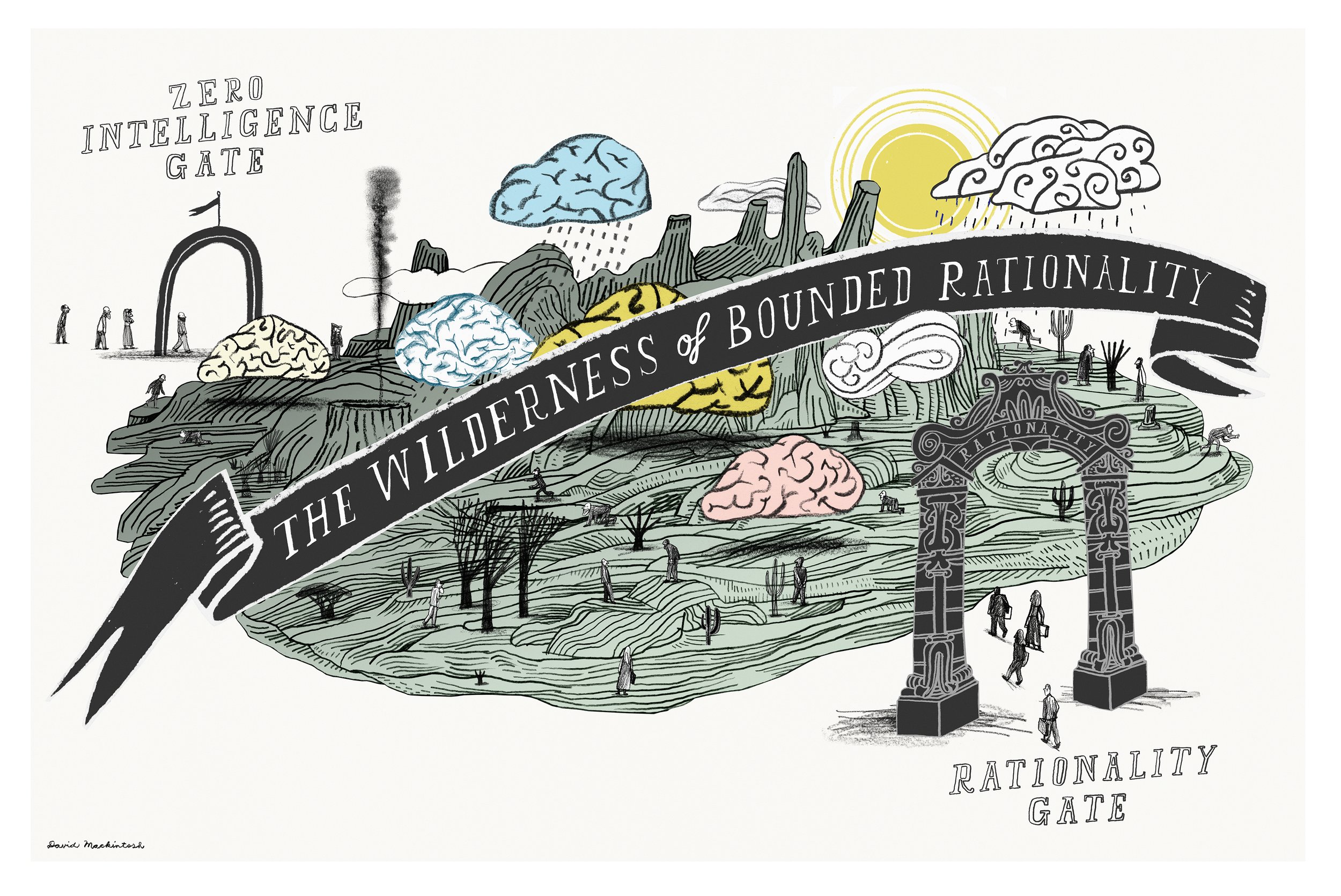

© David Mackintosh 2023.

© David Mackintosh 2023.

The agent-based modeling approach starts from the zero intelligence gate, with the heuristics representing assumptions about real human behavior. These heuristic assumptions sacrifice some of the simplicity of a Rational Economic Actor for a more accurate picture of human behavior. Indeed, complexity economists like Farmer have achieved some success predicting things like real estate prices during COVID — cases where behavior is more determined by heuristics than by rational profit-maximization.

But then, maybe the complexity scientist realizes they are still making too many assumptions — what they really want now is a pure big data model that will make no assumptions about human behavior. Can that be so hard?

3. ToothFormer: A Foundation Model for Toothbrushing Behavior

This is where some crackpot inventor at a big tech company would decide to abuse the GPU budget by training a foundational model to predict toothbrushing behavior. Ignoring computational constraints, one way to do this would be to record people’s entire waking lives, and then train a model to predict how much people brush their teeth based on footage of their waking lives.

Given enough data, I have a feeling that ToothFormer would do a pretty good job predicting how much people brush their teeth. But what new understanding would we achieve from such a model? In order to learn anything new, we would have to try reverse engineering the model’s “knowledge” from its neural network weights, kind of like what Anthropic did with its mechanistic interpretability paper. In the case of ToothFormer, we might imagine learning that certain behaviors — say, taking showers or going on frequent first dates — are closely associated with increased toothbrushing behavior. Notably, however we could not make any causal claims based on the model alone without testing those assumptions in simpler models.

The example of ToothFormer points out one key limitation of big, black-box models of human behavior, which is that they don’t really give us new knowledge about causes and effects — which is what we would need to make policy interventions. Even if the model encodes certain causal relationships, disentangling those causal relationships from the embeddings space of the model would be a task not necessarily simpler than disentangling causality from the real world, which is why the simple models of economics still feel like a much better guide for policymakers.

But the superiority of simple models in guiding action might be a temporary issue — perhaps new methods in black-box model interpretability will make it easier to develop policy-relevant knowledge from large models trained for prediction.

4. Tradeoffs between Predictive and Explanatory Power

At last, we have a decent explanation for why economists seem to be less interested in foundation models than, say, meteorologists. Accurate weather prediction is useful regardless of whether we understand how the prediction is made. Meanwhile, prediction of something like housing prices is complicated for two reasons:

- Let’s say you have a perfect prediction for housing prices. Then publishing your prediction will influence the eventual outcome by convincing people to buy and sell houses.

- In domains of human behavior, the prediction itself affects the outcome

- Given (1), maybe the best you can hope for is a counterfactual model — that is, given a certain set of behavioral assumptions and real-world events, what will happen?

- But black-box foundation models might not predict counterfactual impacts well.

- More importantly, the models would yield few actionable insights for policy, and knowing the housing market will crash won’t help us much unless we know what levers we can push to change it.

Given these limitations, even if foundation models play a substantial role in predicting economic behavior, we still need simple models as a guide for real policy decisions. In a way that’s unique compared to weather prediction, models of economic behavior critically depend on assumptions about human agency. At least in the near-term, then, explanatory power seems like a much more important trait to look for in economic and psychological models.

In fact, explanatory power might be the only thing we should care about in general, with prediction being one useful way to test explanations. This is well captured in the following quote from physicist David Deutsch in The Beginning of Infinity:

The ability to create and use explanatory knowledge gives people a power to transform nature which is ultimately not limited by parochial factors, as all other adaptations are, but only by universal laws. This is the cosmic significance of explanatory knowledge – and hence of people, whom I shall henceforward define as entities that can create explanatory knowledge.

Fortunately for researchers in economics, psychology, and complexity science, the function of science as an explanatory discipline does not seem easy to replace using black-box models. This explanatory function feels especially relevant in the social sciences, because so much of our decision-making depends on our own narratives about human behavior. In the long term, what really matters is not just our ability to predict the future but also our ability to tell a compelling story about where the future will take us.