Anthony Zhou

Psychology, Economics, Programming, or anything interesting.

Hello, I'm Anthony.

CS @ Columbia University '25 | New York, NY

Recent Blog Posts

For more informal writing, visit the writing page.

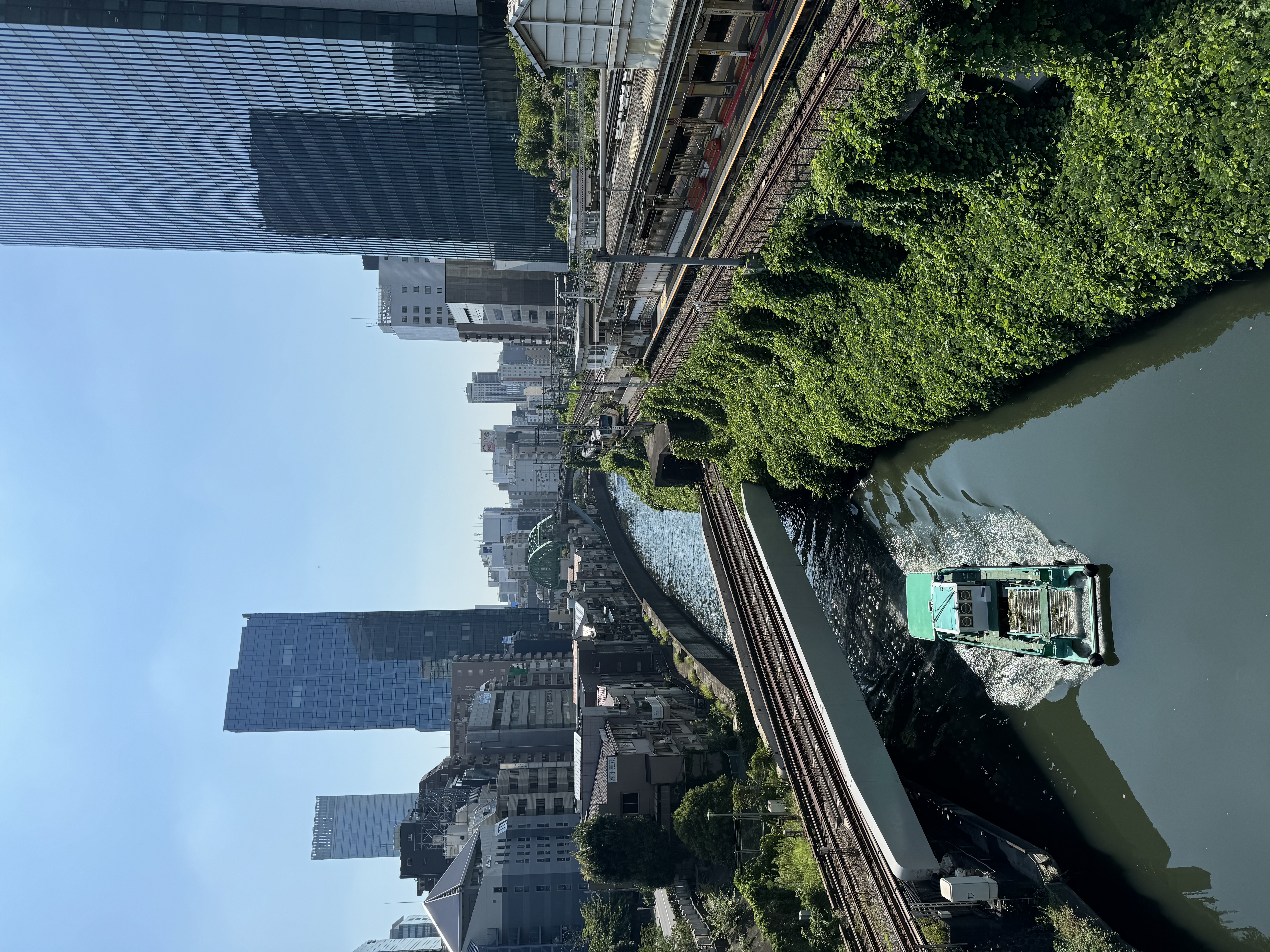

A view from my morning commute.

Quotes and Links

Pragmatism in practice

By anthony | 4 Dec 2024

"'[J]ustice is no more reasonable than what a person's prudence tells him he must acquire for himself, or must submit to, because men cannot afford justice in any sense that transcends their own preservation.'" (pp. 112, directly quoted from Harvey C. Mansfield's translation of Machiavelli)

I Contain Multitudes: two highlights from the book

By anthony | 8 Oct 2024

Darwin, Wallace, and their peers were particularly fascinated by islands, and for good reason. Islands are where you go if you want to find life at its most outlandish, gaudy, and superlative. Their isolation, restricted boundaries, and constrained size allow evolution to go to town. The patterns of biology resolve into sharper focus more readily than they would do on the extensive, contiguous mainland. But an island doesn't have to be a land mass surrounded by water. To microbes, every host is effectively an island -- a world surrounded by void. My hand, reaching out and stroking Bab at San Diego Zoo, is like a raft, conveying species from a human-shaped island to a pangolin-shaped one. An adult being ravaged by cholera is like Guam being invaded by foreign snakes. No man is an island? Not so: we're all islands from a bacterium's point of view.

Standing on the shoulders of a pyramid of hobbits

By anthony | 16 Sep 2024

So yes, we are smart, but not because we stand on the shoulders of giants or are giants ourselves. We stand on the shoulders of a very large pyramid of hobbits. The hobbits do get a bit taller as the pyramid ascends, but it's still the number of hobbits, not the height of particular hobbits, that's allowing us to see farther.

On Meritocracy

By anthony | 15 Sep 2024

Barack Obama's 2004 speech at the Democratic National Convention is often considered the starting point for his eventual presidential career. He begins the speech with a touching account of his family history (source):

The cold start problem

By anthony | 15 Sep 2024

Thus, the start-up problem means that the conditions under which there's enough cumulative culture to begin driving genetic evolution are rare, because, early on, there wouldn't have been enough of an accumulation to pay the costs of bigger brains. And if there had been, the most adaptive investment would be in improved individual learning, not better social learning or eventually cultural learning. So in order for natural selection to favor improved social learning, there has to be a lot of cultural stuff to learn, but if you don't have much social learning, there's unlikely to be much of an accumulation out there to tap.

The Dispossessed

By anthony | 9 Sep 2024

In Stillness is the Key, Ryan Holiday retells the story of Epictetus, As a young adult, Epictetus (a notable Stoic) had a cheap earthen lamp that he used regularly. Once he got richer, he bought a nice cast iron lamp to replace the earthen one.

Development abstraction layer

By anthony | 9 Sep 2024

One blog post that I keep coming back to is Joel Spolsky's article on The Development Abstraction Layer:

What should we make of Cocomelon?

By anthony | 7 Sep 2024

I was prompted to think about Cocomelon by a recent interview on the Ezra Klein show with the writer Jia Tolentino. It's a fascinating topic. It's very common these days to see toddlers with their screens glued to an iPad. Having met some of these toddlers myself, I think there's a good chance they're watching Cocomelon. Cocomelon, and shows like it, are part of a new wave of media that specifically targets toddlers. It's ridiculously popular -- increasingly so. But what should we make of its popularity?

A million miles in a few hours: book review

By anthony | 6 Sep 2024

This morning, I started and finished the memoir A Million Miles in a Thousand Years: How I Learned to Live a Better Story by Donald Miller.

Subscribe to updates on Substack

Subscribe to updates on Substack